In the laboratory, the world is clearly defined: Permeation measurements on packaging films are usually carried out at 23 °C and defined relative humidity levels, typically 50% RH or 85% RH. These conditions are established in standards (e.g. ASTM F 1927 (2014), ASTM D 3985 (2024), DIN 53380-3 (1998-07), for oxygen permeation) and are easily comparable and widely accepted in the industry.

However, food is almost never stored in this way in practice.

Many products are stored for weeks or months in refrigerated shelves, in the freezer section or at moderate room temperatures, often with significantly lower humidity than in the standard climate.

The upcoming changes to packaging systems – such as PPWR, mono-materials and recyclability – mean that a key question must be answered:

Are we actually testing our new, recycling-optimised packaging solutions under conditions that are truly relevant in practice?

Standard conditions vs. practical reality

Currently, “everyone” – as can be read in many specialist publications and newsletters – measures at 23 °C / 50 % RH or 23 °C / 85 % RH. These conditions are useful when it comes to comparability and worst-case scenarios.

But anyone who takes a look at the actual logistics chains and storage conditions will quickly realise that:

- Chilled products are often stored at around 4–8 °C and moderate humidity.

- Some barrier concepts are less affected by humidity and temperature stress when transporting frozen products.

- Even at room temperature, many applications tend to be around 20–22 °C, not 23 °C with 85% relative humidity.

The consequence:

It is important to note that any individual who evaluates packaging, particularly novel structures optimised for recycling, such as BOPP/PP copolymers, exclusively under “classic” laboratory conditions and compares it with established compounds, such as PET/PE runs, risks setting barrier requirements too high.

The differences between ‘traditional’ high-barrier composites and new PPWR-compliant solutions are likely to be significantly reduced under milder, more practical conditions than is currently assumed.

Focus on EVOH: When does moisture become truly critical?

EVOH (ethylene vinyl alcohol) serves as a prime exemplar of the interplay between climate and barrier properties. EVOH is established as an oxygen barrier; however, it exhibits a pronounced moisture dependence:

- At higher relative humidity, EVOH absorbs water.

- the oxygen barrier deteriorates.

- the measured OTR (Oxygen Transmission Rate) increases.

The exciting question is therefore:

How long does it take for an EVOH composite at 23 °C / 75 % RH to show a relevant change in OTR due to moisture absorption compared to 6 °C / 75 % RH?

Applied to practice, this means:

- Under refrigerator conditions (e.g. 6 °C), the “breakthrough point” – i.e. the point at which the oxygen barrier of an EVOH system becomes truly critical due to the effects of moisture – could potentially be well beyond the best-before date.

- In other words: for many cooling applications, the theoretically possible deterioration of the barrier in standard climate conditions below 23/75 would be virtually irrelevant in the actual life cycle of the packaging.

This thesis is highly relevant – especially if classic PET/PE composites are to be replaced by new, more recyclable structures. It also shows how important it is to parameterise permeation measurements not only in accordance with standards, but also in a practical manner.

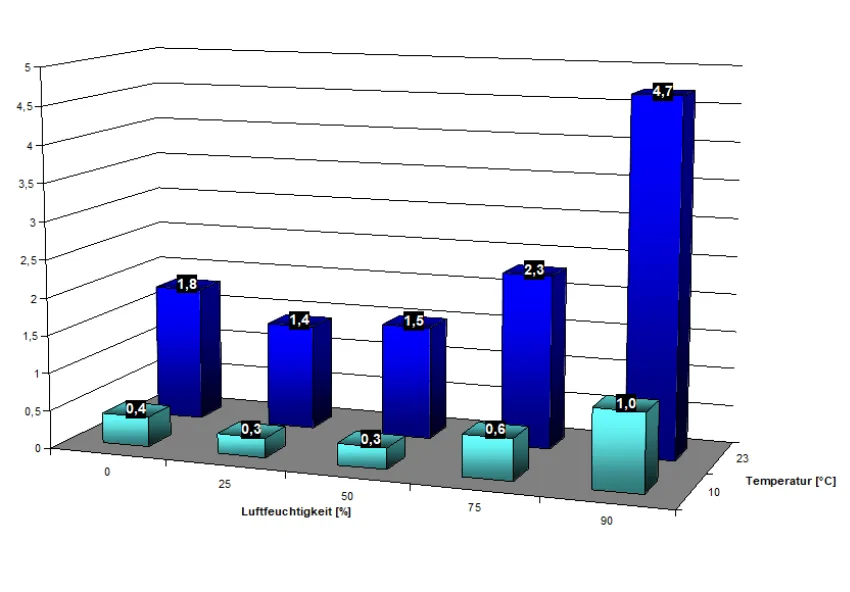

Dependence of the permeation rate on different relative humidities and temperatures (source: ppg<) (Luftfeuchtigkeit: Humidity)

Hygrothermal permeation measurements: A realistic look at new packaging systems

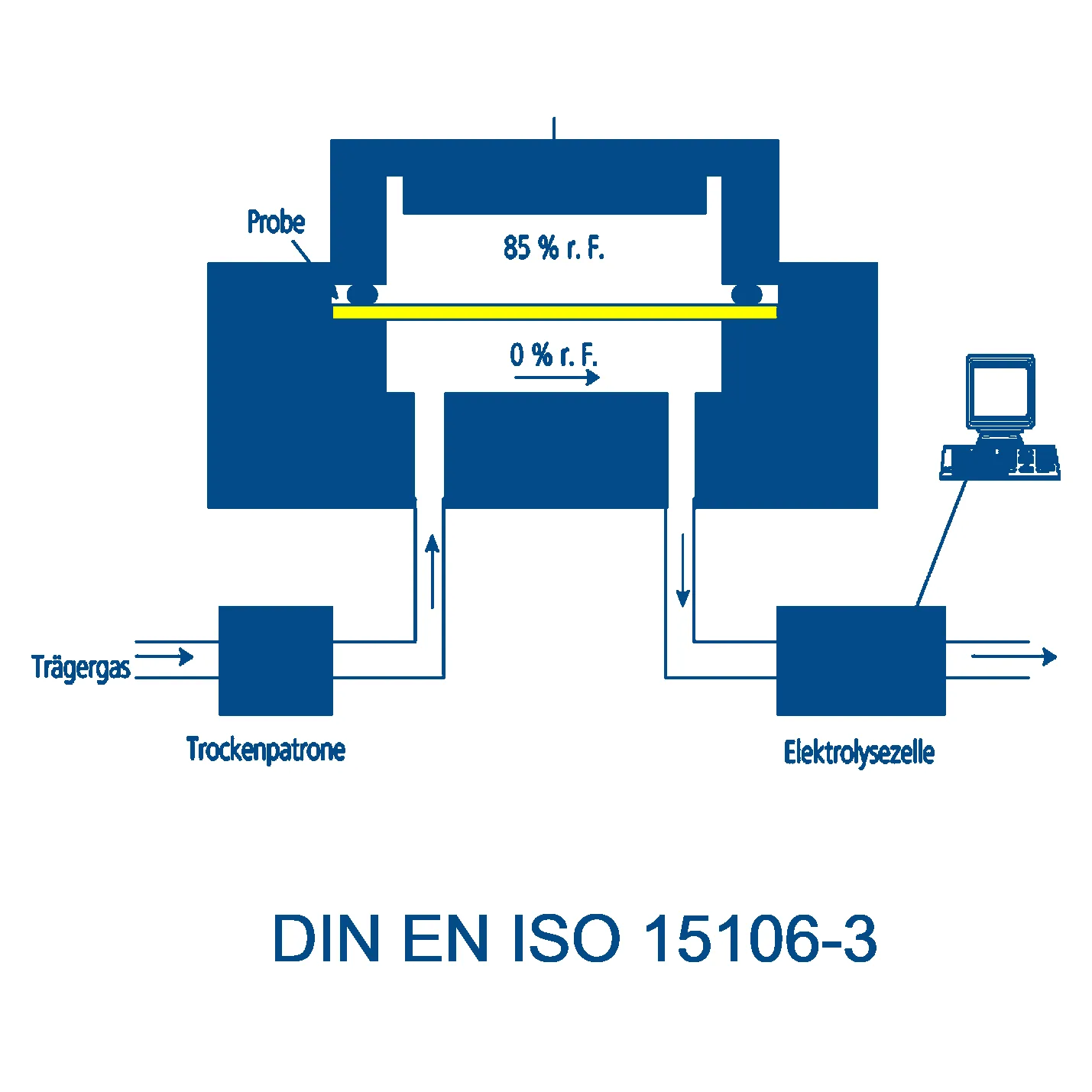

In order to answer these questions in a well-founded manner, hygrothermal measurement series are required, i.e. systematic permeation measurements using different combinations of:

- Temperature (e.g. 6 °C, 10 °C, 23 °C).

- relative humidity (e.g. 50%, 75%, 85% RH).

Modern measuring systems now make it relatively easy to map such climate profiles. When used in a targeted manner, this opens up new possibilities:

- Simulation of realistic storage conditions for refrigerated and room temperature products.

- Comparison of “traditional” and “PPWR-optimised” packaging under conditions that correspond to actual practice.

- Determination of breakthrough times for EVOH or other barrier concepts over time and under varying climatic conditions.

This could be used, for example, to investigate:

- How does the OTR of an EVOH composite change over the storage period at 23/75 compared to 6/75?

- At what point – and at what combination of temperature and humidity – does barrier deterioration become truly relevant for a specific product?

- How do classic composites (e.g. PET/PE) fare in direct comparison to OPP/PP copolymer structures when considering not only extreme laboratory conditions but also the actual supply chain?

Why this should be of interest to food manufacturers and packaging suppliers

For food manufacturers and packaging suppliers, these questions are by no means academic. They concern very specific decisions:

- Conversion of existing packaging systems from PET/PE or other traditional composites to more recyclable solutions, such as OPP/PP copolymer or other monomaterial concepts.

- Definition of specifications: Which OTR and WVTR limits are really necessary if, for example, the product is stored in a permanently cooled environment?

- Risk assessment: In which scenarios is a theoretically poorer barrier in the standard climate actually critical – and in which scenarios is it not?

If it turns out that, under practical, milder conditions, the barrier differences between known and new, recyclable packaging are smaller than expected, this could:

- accelerate the use of more sustainable packaging.

- put excessive safety margins into perspective.

- and objectify the discussion about “functional barriers vs. recyclability”.

In short: Those who ask the right questions about permeation gain a head start in designing sustainable packaging solutions.

Conclusion: Rethinking permeation measurement – in terms of practical application

Permeation measurements at 23 °C and 50 or 85 % relative humidity remain important – they are established, comparable and enshrined in standards.

However, given the profound changes in the world of packaging, it is no longer sufficient to focus solely on the regulatory environment.

- Food is rarely stored at standard climate conditions.

- Barrier concepts such as EVOH are sensitive to moisture – though the relevance of this sensitivity remains to be determined.

- New PPWR-compliant packaging deserves to be evaluated under conditions that correspond to actual storage and transport conditions.

Hygrothermal permeation measurements, in which temperature and humidity are varied in a realistic manner, offer significant added value here. They help to define barrier requirements realistically, conserve resources and, at the same time, ensure product safety and quality.

This is precisely what food manufacturers and their packaging suppliers should be interested in, as it is crucial to avoid oversizing and the subsequent costs that arise from it. It is also an ideal field in which to fully exploit the possibilities of modern permeation measurement technology.